A Performance to Forugh and An Incomplete

Forugh Farrokhzad was born on 5 January 1940 and passed thirty two years later, on February 13. At the time she was the most important contemporary poet of Iran. A poet who was not much liked by the cultural canon and the male world, for she would break the laws of their world in both life and poetry, which were one and the same. In homes they were not so eager for their youth, especially their daughters, to read her poetry — they were considered loose. Men were allowed to do that. But we read and grew up and lived with her poetry.

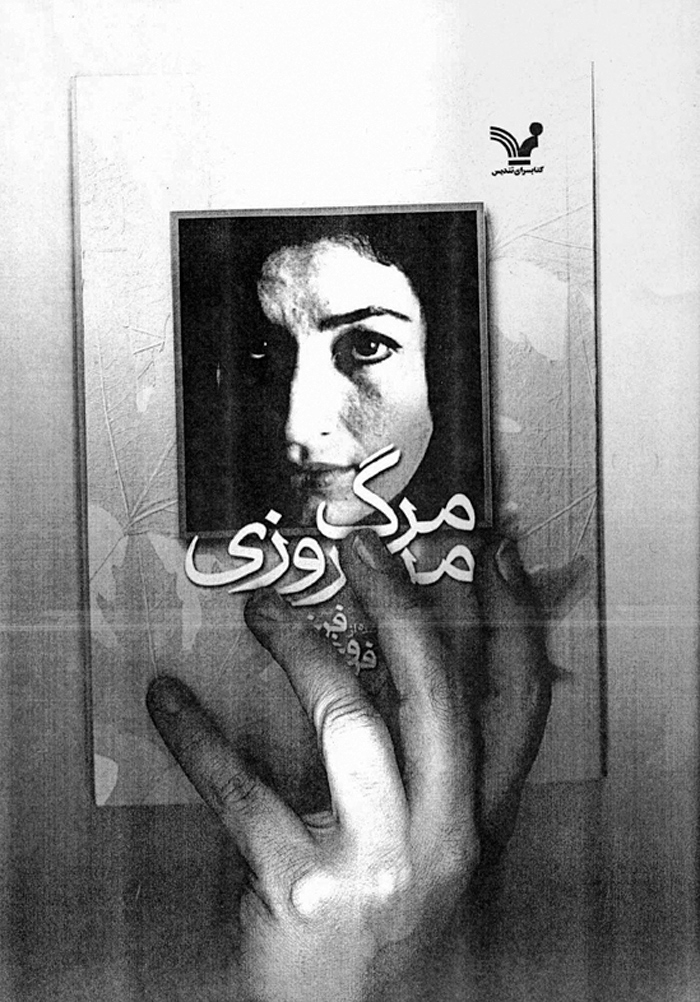

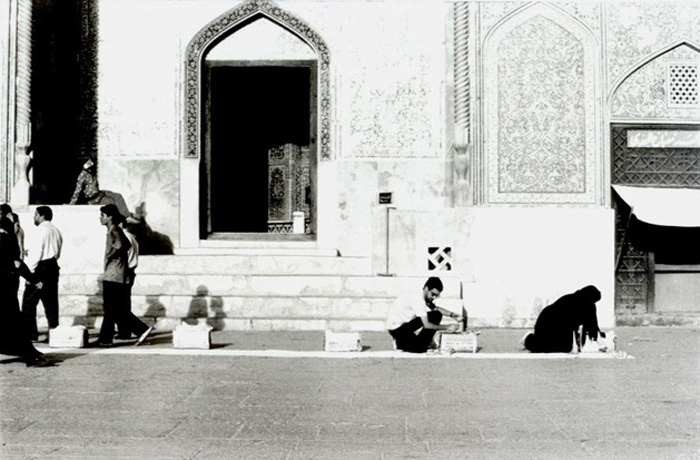

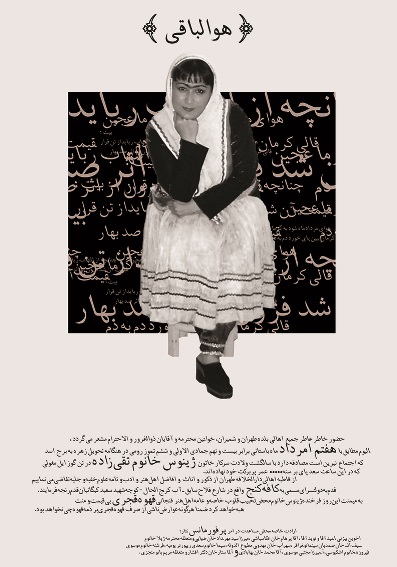

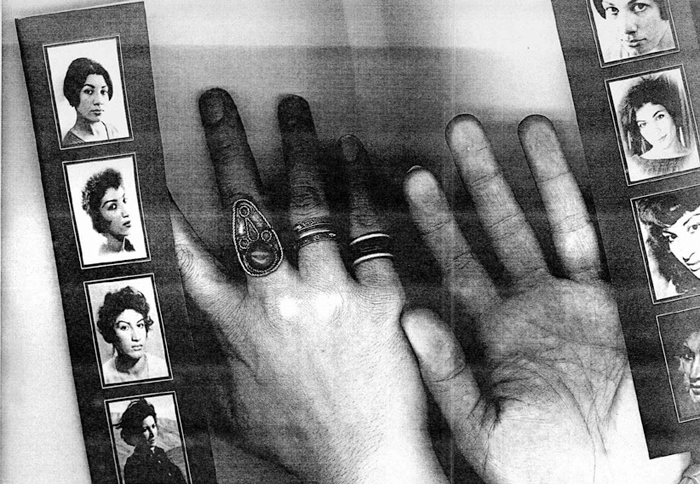

Two years ago (2004) on her birthday, I prepared a street performance for I believed observing her birthday was more important than wailing her absence. From a bookstore in Bagh-Ferdows in northern Tehran, I set off for Zahir od-Dowleh Cemetery, the poet’s final resting place, with an arm full of posters, a bucket of glue and a brush, like city workers. I had photocopied pages of Forugh’s books and her photographs. I had printed my hand, complete with finger-rings, over these images, as if to leave my own mark on her poetry — Forugh.

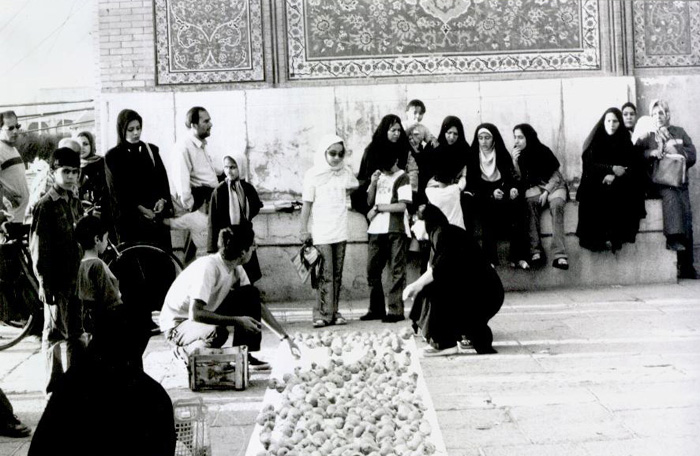

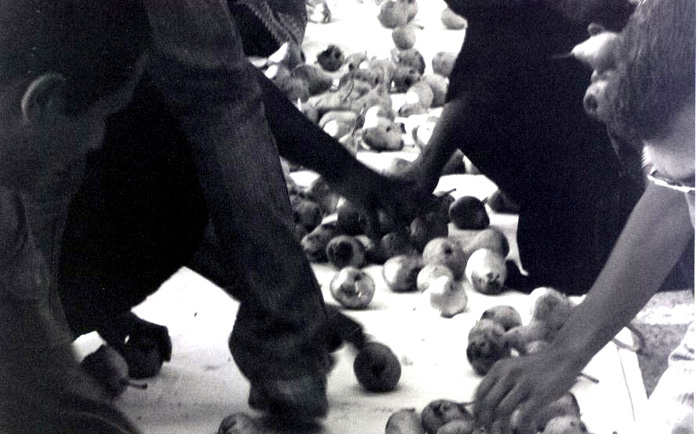

Neither my appearance nor what I was gluing to the wall looked like what a city worker would do. People gathered, started reading or checking it out. The elders, the same ones who for a lifetime had forbidden Forugh to their sons and daughters, quickly recognized the face and the poetry — perhaps in secret many had read her. And the younger people seemed to have seen her before. You may refuse to accept Forugh but you cannot ignore her. In a politicized city such as Tehran, many quickly connected her to the current political issues. Here and there they stood around the pictures in discussion. During a three-hour-long walk, the route was filled with posters, even though twice the city workers and police tore the papers off the walls and took away the glue and brush with threats. But in the afternoon, if you would follow the images here and there, you will reach her grave, under the light snow fall of which a small crowd had celebrated her birthday with a small cake.

My plan had been to have another performance 14 days later on the anniversary of her death and follow the same route with a backpack filled with a blue-colored powder. A backpack punched with a hole which would mark the entire route with blue paint. If you were to follow the blue paint, you’d reach Forugh, Forugh Farrokhzad. The heaviest snow of the year fell and I was stuck…. Now maybe this year….

“Forugh Performance” Gallery